‘The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn and relearn’ Alvin Toffler

The American futurist Alvin Toffler was acutely aware of the seismic changes that society was facing when he wrote his best seller Future Shock in 1970. He saw the fundamental transformation of societal structure and values since the industrial revolution through to the technological age as all pervasive and constantly accelerating. His prescience was striking, as so much the world of the 70’s is unrecognisable from the one we live in today, in areas such as employment, technology, personal identity and the media.

Education has changed enormously in that time too, of course, although the structure of the school year and the way we run them in classes and year groups has, in fact, not really altered much since the industrial revolution. However, one recent shock that even Toffler could not have foreseen has, arguably, had a bigger impact on pedagogy and schools than decades of political machinations and assessment changes.

The Covid pandemic forced educators to think about teaching and learning in a completely new way. Distance education was an immediate priority for families and teachers, who, along with most other people, became experts in video conferencing overnight. The new learning that went into this process happened on a scale never before seen in our educational establishment. Managing the education of 20+ young people in a classroom is no easy task, but replacing that with the complexities of delivering stimulating lessons, monitoring progress and providing meaningful feedback for improvement in an online setting – this called for skills that had barely been tested in most schools.

Ironically, developing this new approach often involved ‘unlearning’ old ways of working, both for students and teachers. The new pedagogy could not rely as much on teachers being present with students when the learning took place. Learning became more ‘blended’ with teachers working as facilitators for more of the time, rather than instructors. This led to students who could take more initiative, working collaboratively with other learners and assuming more responsibility for how they gathered information and developed their knowledge. The teacher is certainly essential to this arrangement, to lead the learning, encourage participation and ensure accuracy, but student independence is the key to success. After all, is it not generally better to learn to make your own dinner rather than calling for a takeaway?

Clearly, these dispositions are hugely positive for learners. However, the wellbeing benefits of being together physically in a learning environment became increasingly obvious as time went by under lockdown. Within classes now, students and teachers can make use of the new ways of working that we developed in lockdown, often with the help of EdTech, while benefiting from the calming social structures of physical school to create a more blended approach to learning. Teachers can choose which parts of a lesson lend themselves better to individual study, or group instruction, and which parts work better with a collaborative approach. Students who are self-isolating can also dial into these lessons and not feel as though they are working in a vacuum. All this leads to a virtuous circle where anxiety is reduced and confidence is built through a group dynamic, which leads to deeper and more fulfilling learning experiences for all.

The challenge for schools now is to resist the temptation to relearn what we have unlearned; to continue to learn how to do better things instead. Our focus must be to unlock even more potential and to imbue students with the key intellectual character traits, such as adaptability and independence of thought, that will allow them to face an uncertain future with a smile. To give them the confidence to know they have the skills and dispositions to be fully ‘literate’ and can flourish in the fluid employment market they are entering.

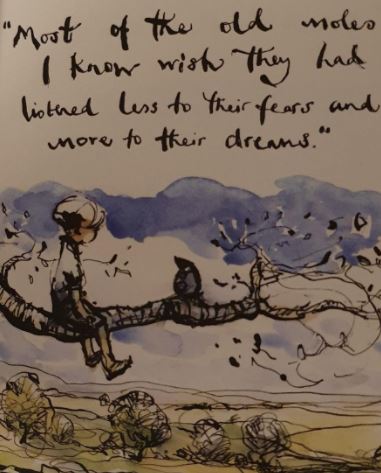

As the mole so rightly tells the boy in Charlie Mackesy’s zeitgeisty modern classic The Boy, The Mole, The Fox and The Horse, ‘most of the old moles I know wish they had listened less to their fears and more to their dreams’. If fear of failure is something that can be unlearnt then we can all be confident of a better future.

Henry Rickman

Deputy Head Academic

The Boy, The Mole, The Fox and The Horse, Charlie Mackesy, Ebury Press, 2019

Future Shock, Alvin Toffler, Random House; 1970